Since my last blog on transition, I’ve been surprised at how quiet things are on this topic. At the PAS conference (Wolverhampton, July 2022) I presented a few ideas and hypotheses about the transition from the present planning system to the new ‘Levelled Up’ one. These are set out below along with some feedback from the conference attendees.

Some movement starting…?

The recent letter from Greg Clarke urging PINS not to fail Local Plans over the Summer may signal that some announcement is afoot (the heralded NPPF prospectus?) in Autumn. And the announcement from Dorset that ‘having spoken to Government’ that they’ll be taking a further few years to adopt their plan and (most interestingly) that they have asked to be ‘part of a pilot for a new national approach to local plans’.

Why is it quiet?

Parts of the Levelling Up & Regeneration Bill (LURB) are receiving lots of attention e.g. the new Infrastructure Levy or being PAS work-shopped (Environmental Outcome Reports). Other parts are slowly becoming embedded such as design codes and the (oh so slowly) creeping digital agenda. But its largely silent on how we move to a new system for making a local plan – the thing that is going to hold all of this together.

In May the then Minister Stuart Andrew encouraged us to ‘keep on planning’ and that transitional arrangements were being worked on ‘at pace’. There was also some early conjecture about incentives to get your plan in place as soon as possible (e.g. that the 5-year housing land supply requirement may disappear for up-to-date plans).

December 2023 – an incentive?

DLUHC seem to have stopped referring to this date, however I am working pretty much exclusively with councils going full steam ahead to get plans in place by Dec 2023. Over half the councils at our conference are as well. Greg Clarke’s recent letter to PINS may spell good news for these councils, especially those at examination right now. For these councils, the requirements of straddling 2 systems while plan making will be for others to grapple with. It is the councils that are about to start a review of their plans that are going to have to pick up the baton on transition soonest – they’ll be the front runners that will be learning how to plan in the new system.

The biggest change/challenge is the timetable

Take away all of the noise, the aspiration and the detail (where there is any) and the LURB system local plan and process looks pretty similar to what we currently have – policies, maps, 2 consultations, examination.

The big change is the expectation that the plan making timetable will be CUT IN HALF from an average 5 years to 30 months. Everything that LURB is proposing on plan making will need to be condensed into at least half the time it currently takes. That is eye-watering. The ‘speeding up’ comes from 2 broad directions:

- The mechanics – there are the new time-saving elements to factor in; front-loaded consultation, National Development Management Policies (NDMP’s), streamlined (proportionate?) evidence bases, mandating infrastructure providers to engage, Environmental Outcomes Reports (EORs to replace SA/SEA) – all good ideas to save time.

- The process – the proposals for local plan commissioners, Gateways Reviews, a replaced Duty to Cooperate – again all good ideas on paper but how will they work to reduce time in the overall process?

There has to be enough time factored in to learn about, test and integrate these new and adapted processes into our plan making activity. How can we avoid a standing start? Hopefully more detail on these individual ‘speeding up’ elements and how they will all work together will be available soon. Once the detail begins to emerge, we have to be prepared / make time available to learn and bed things down. Anyone that has been in the improvement game knows that introducing improved ways / systems of working often causes a system to slow down in the short-term. Room and time have to be allowed to allow the changes to take root and for the first positive effects to begin to show and the learning transferred.

Less burden has to be accompanied by less risk

While changing the mechanics and inputs to the process we must also keep an eye on the more structural (and cultural to some extent) aspects of plan making that will need to change/adapt to make a new system work.

I can see how we will over time reduce the burden on evidence base production via digitisation as the updating of evidence in future becomes more streamlined, however there will be a period of bedding down. To deliver a system that requires a shorter and less information-intensive approach (e.g. 50-page Environmental Outcome Reports replacing sustainability appraisals) and a more proportionate and streamlined evidence base, the plan examination system has to adapt with it. There should also be some built-in recognition of / protection from legal challenge; QC’s are expert at finding chinks and gaps in the masses of evidence that support plans currently – how will a radically reduced evidence base hold up to the same scrutiny?

Front-loaded consultation and digitisation are heralded as the panacea’s for greater and better community consultation, and I think this is a broadly correct assumption. It does have to be more than reaching wider audiences through technology and presenting our plans and ideas on maps and using 3-D imaging – there is a fundamental requirement to make planning simple to understand – e.g. nothing digital or map-based is going to explain to our communities in logical terms how we currently arrive at the housing numbers we’d like them to accept. We can and must get better at all of this and we have to also be prepared to resource, manage and integrate greater levels of engagement as communities do become more planning ‘savvy’ and want to get involved to support and challenge what we are proposing in our local plans. Levels of engagement are already rising as communities, especially in constrained, and more and more councils are struggling to resource ever-growing consultation responses.

Transition basics

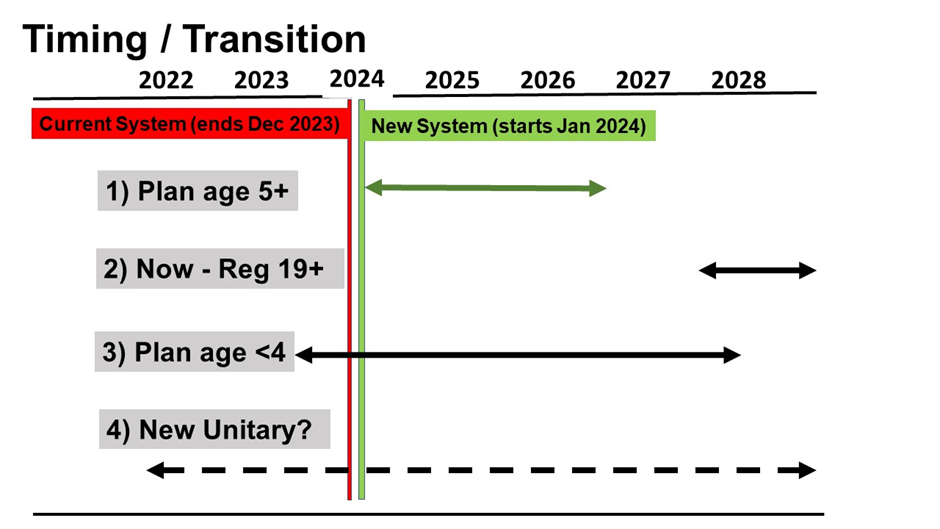

Back to my conference story. For the sake of starting a conversation/argument I presented a few made-up hypotheses about what transition might look like in terms of timing. Here’s what I set out:

- Hypothesis 1 – December 2023 – the drawbridge goes down on ‘current system’ – councils will have to have their plan submitted by December 2023 otherwise the plan has to be prepared and produced in the new system under transitional arrangements.

- Hypothesis 2 – January 2024 – New NPPF and Regulations are set with the requirements for new system local plans

In this world, councils will fall into 4 broad categories:

- New System Plans – those councils intending to wait and begin their plan making process after January 2024. The first plans will be in place from June 2026.

- Current world plans submitted on or before end December 2023 – Those that submit their plan to the December 2023 deadline and will arguably not have to think about starting the process of getting a new system plan in place before 2028.

- Current / New World transition – those councils starting to review their plans now will find themselves straddling the current and new system completely – it’s for these councils that the transitional arrangements need to be clear – not least to avoid wasted work.

- New Unitary councils – have 5 years to get a plan in place – will/how will the transitional arrangement affect them?

So what to do in the meantime?

I understand the reasons so many plans are stalling and why many are waiting for the new system. Why carry on if a new NPPF (prospectus?) is imminent? Why waste time, effort and cost? Then there is the hoped-for arrival of lower housing numbers. But is this really doing the best by our communities? The waiting game comes with risk as local plans and polices age and become vulnerable to speculative development and confuses communities as plans are ‘pulled’ to protect them from too much development (housing) and then housing sites are granted permission on appeal and in places not even allocated in the plan.

My view – keep going where you possibly can

I am asked constantly by councils for my advice on pressing ahead/slowing down/stopping. My (non) answer is always the same; I ask the following 3 very broad questions;

- Do you have clear evidence that delaying, slowing, stopping the local plan will benefit all of the communities your council represents?

- Have you fully weighed up and quantified the risks / uncertainties for your place that the absence of an up-to-date plan creates for your communities and investors?

- Do you have the backing of your communities / investors for your preferred course of action?

The reasons for stopping and delaying can be either very narrow; “housing numbers are going to change” or very broad; “it’s too uncertain right now”. The narrow arguments betray a massive misunderstanding about what the local plan is there for and that housing, while important, is not the only thing we plan for. The broader argument just doesn’t hold water – the world we plan in is constantly uncertain, it is one of the fundamental reasons we make plans in the first place.

Plans will always needs evidencing, consulting on and need some form of testing/examination so I personally would recommend that councils keep their plan making and plan updating activity going. And I urge the government to consider in its transitional arrangements how it can reduce any burden (perhaps even ‘rewarding’) those councils that are, despite massive pressure to slow down or stop, demonstrably carrying on planning and trying to get their plans updated and in place.